Extraction of the Sodinokibi configuration file

Introduction

I recently had the opportunity to work on a Sodinokibi sample but I have not been able to find a beginner-friendly guide to extract its configuration file, so I thought I would try and write one. Sodinokibi is a powerful and efficient ransomware sold and maintained by REvil, and is part of the growing trend of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS). This post will be focused on its unpacking, configuration and some detection artifacts.

Unpacking

I got ahold of some fairly recent samples (May-August 2020) in order to have a more thorough comprehension of how it works.

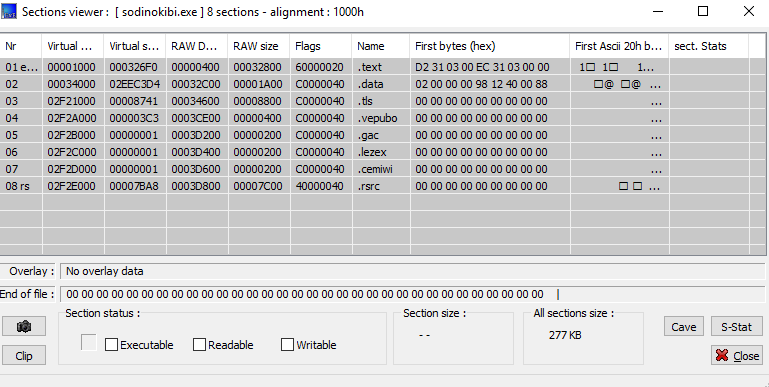

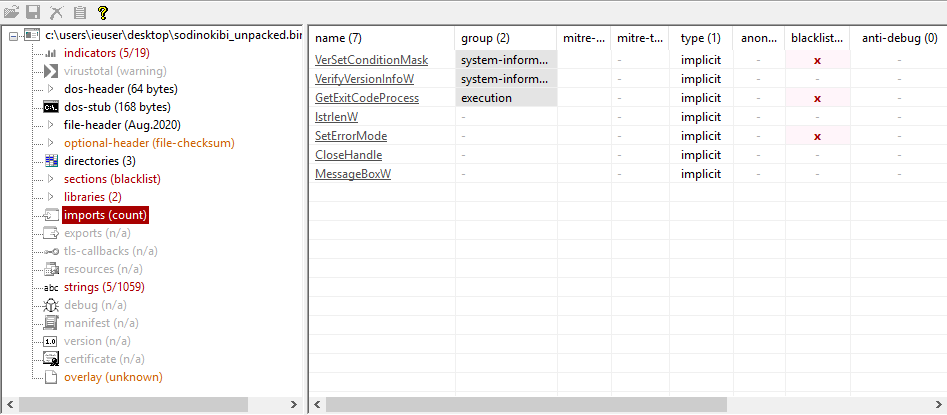

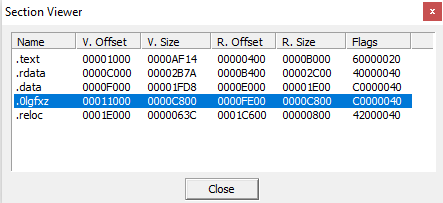

Upon opening the file in a PE viewer I can see that the sections have a high entropy, and that there are some uncommon ones:

ExeinfoPE also suggests that the samples are packed with a custom C++ packer. Checking the behaviour of the sample on online sandboxes quickly shows that there is a single process spawned, and from an unpacking point of view this suggests that either the code is injecting in itself or that it has anti reversing techniques.

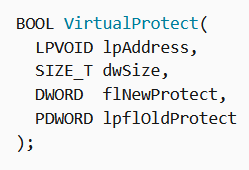

Unpacking the malware is rather straightforward, as the injection happens from within the process. All I need to do is set a breakpoint on VirtualProtect, which will change the protection of the memory region referenced by lpAddress in the space of the calling process, in this case making it executable. Here is its structure from MSDN:

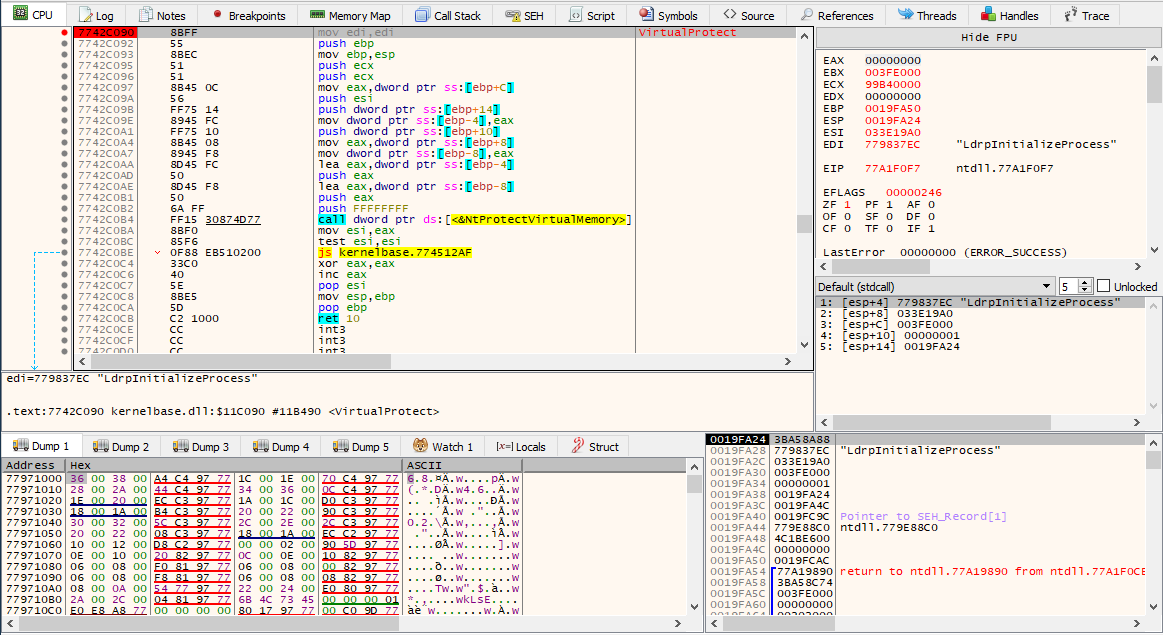

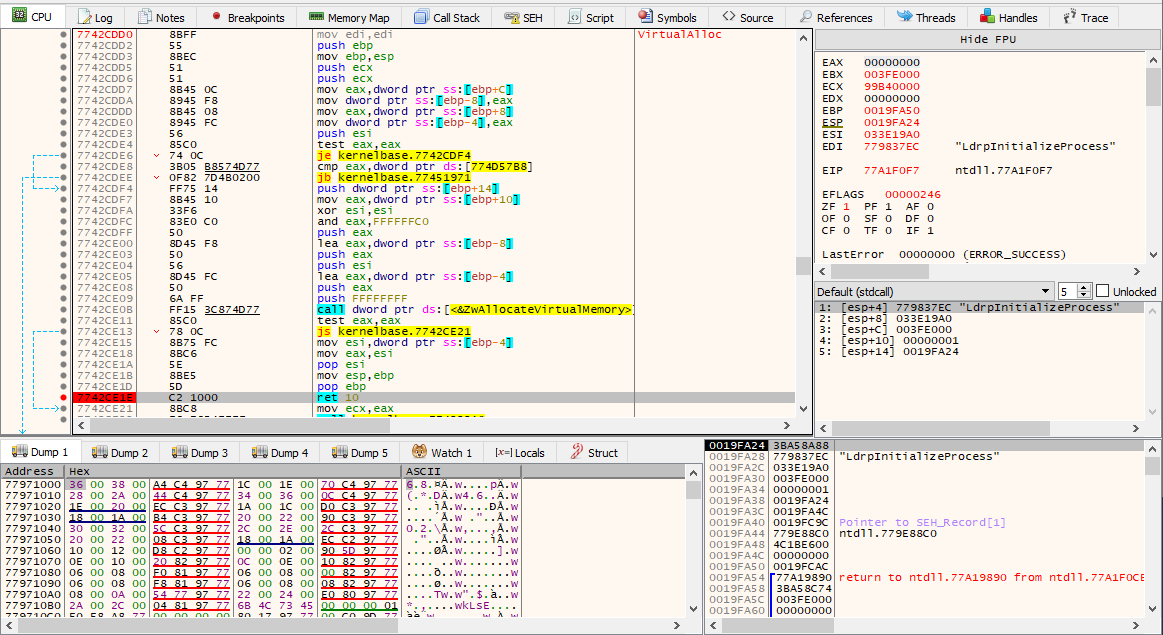

I will also set a breakpoint on the return of VirtuaAlloc, which will contain a pointer to the newly allocated memory region where supposedly the unpacked binary will be written into; this will be loaded into the EAX register.

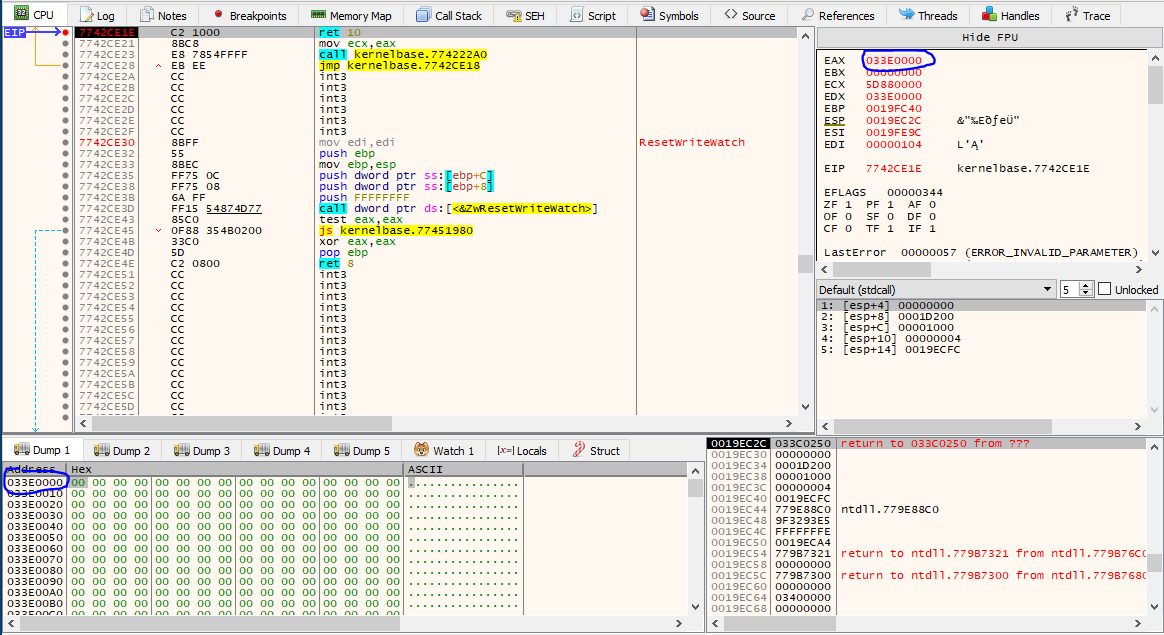

I decided to do so in x86dbg, being more familiar with it. The functions are inside of these sort of wrappers, so all I do is follow the jumps and set the breakpoints.

Breakpoint on VirtualProtect:

Breakpoint on the return of VirtualAlloc:

When I hit the breakpoint on the return of the VirtualAlloc I right-click the EAX register to follow it in memory, because that is the address of the newly allocated region. In fact, it is empty:

At the next run I will hit the call to VirtualProtect, and the dump will have our upacked PE:

The ransomware configuration

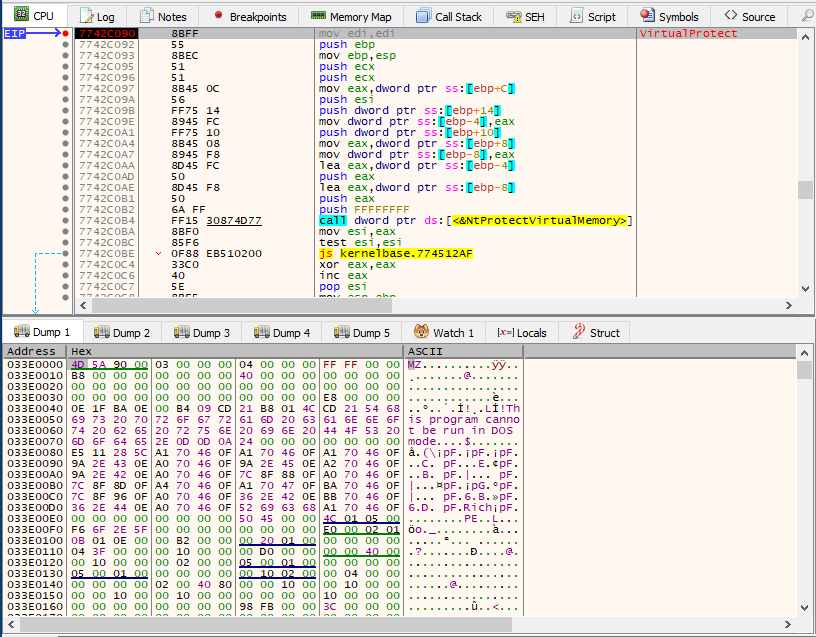

Once unpacked I am able to have a better view of the files content. From PEstudio I see that the imports are somewhat scarce:

That’s because they are hashed. I used a method showed in a video by OALabs to build the IAT using Scylla, even though it is not necessary if one only wants to extract the configuration.

The configuration is stored in a new non-executable section of the PE. I gathered from the samples I have worked on that the section name is made from random letters and numbers. For some reason PEstudio is not able to dump the section correctly, and I have not found an explanation, so I used peid instead, but any other tool will suffice (one could even copy/paste it from the PE).

Sections of the unpacked sample, highlighted the config:

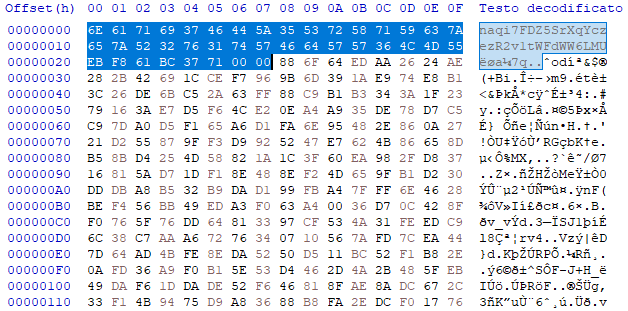

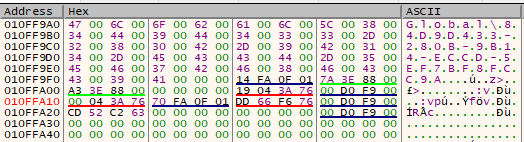

The configuration is a RC4-encrypted json file structured like this:

- the first 32 bytes are the plaintext key to decrypt the config

- the bytes 33 to 36 are the CRC32 of the configuration

- the bytes 37 to 40 are the configuration length

- the rest is the encrypted configuration

This is the beginning of the config, with the first 40 bytes highlighted:

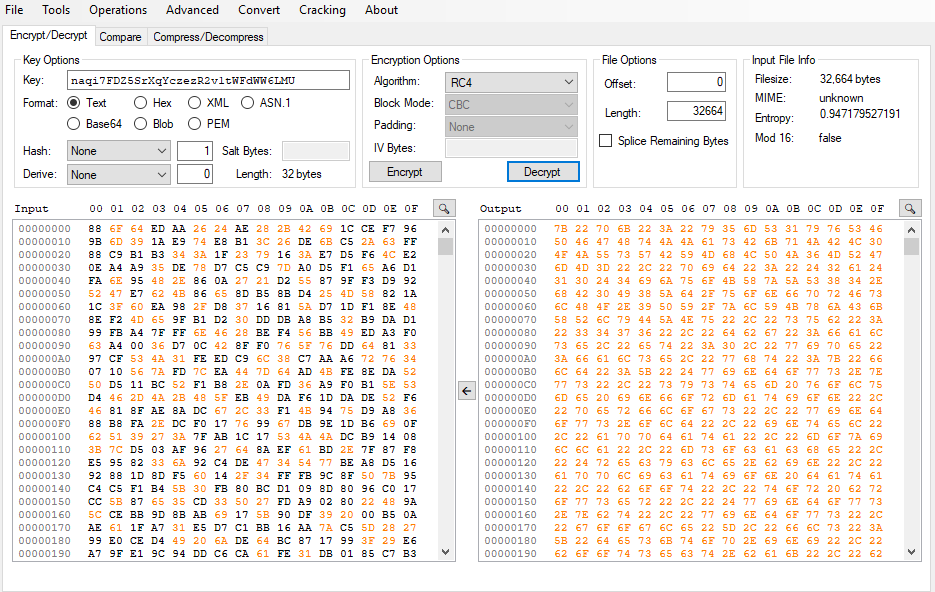

So, in order to properly decrypt the file, I need to remove the first 40 bytes. Notice that if the config starts with a null-byte(s), it will also have to be deleted. I used CryptoTester by Michael Gillespie with the following configuration to decrypt it, but any other tool will do:

(notice the key and that the fist byte of the input is the 41st of the encrypted configuration).

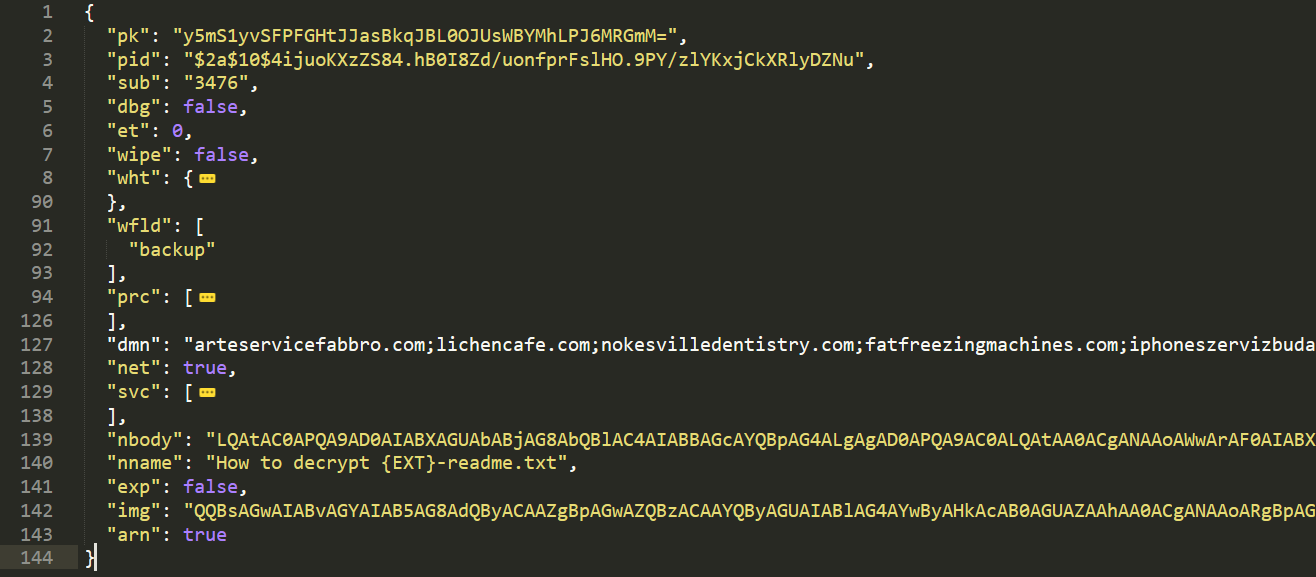

Finally, the configuration is fully obtained by beautifying the json:

A thorough explanation of the fields can be found online (1),(2), some interesting ones are first three:

pk |

attacker’s public key |

pid |

affiliate ID |

sub |

campaign identifier |

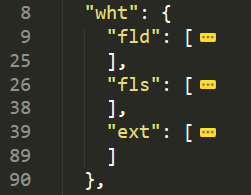

The field wht is also very interesting, as it contains whitelisted directories (fld), files (fls) and extensions (ext) that will be excluded from the encryption process.

The reason for this is twofold: on one hand encrypting every file on a filesystem would take too long and would necessarily encrypt not-so-interesting files to the end-user, which are not the ones for which the victim is willing to pay; on the other hand an encrypted filesystem would not work and would then not be able to offer the possibility to, for instance, download Tor and make the payment. In other words the encryption must be made in such a way, that the system can be fully restored by simply paying.

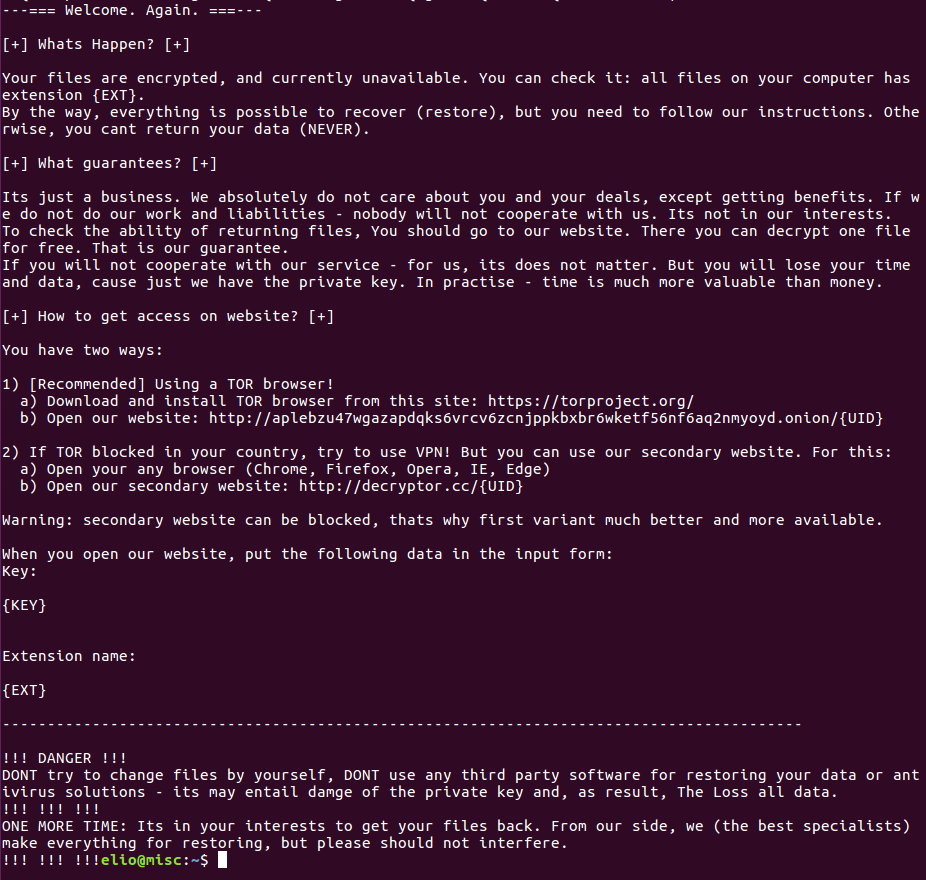

The parameter nbody contains the base64-encoded ransom note. Notice that is has some placeholders like {EXT} that will be calculated during the infection. In targeted attacks, the note can contain information about the victims.

Some artifacts on a compromised system

Sodinokibi will create a mutex using CreateMutexA, here is a screenshot of its value passed to the function:

The ransomware will also attempt to send details of the machine to the list of hardcoded C2 servers in the config (dmn). It will send the contents of the values saved in a key in the registry, so DNS requests to those domains are to be expected on the network.

Other valuable information regarding every stage of the infection can be found here.